Update: Virgin fixed the issue Tuesday night after taking their login page

down for four hours. Please see my update at the bottom of

this post.

The first sentence of Virgin Mobile USA’s privacy policy announces that “We

[Virgin] are strongly committed to protecting the privacy of our customers

and visitors to our websites at www.virginmobileusa.com.” Imagine my surprise

to find that pretty much anyone can log into your Virgin Mobile account and

wreak havoc, as long as they know your phone number.

I reported the issue to Virgin Mobile USA a month ago and they have not taken

any action, nor informed me of any concrete steps to fix the problem, so I am

disclosing this issue publicly.

The vulnerability

Virgin Mobile forces you to use your phone number as your username, and a

6-digit number as your password. This means that there are only one million

possible passwords you can choose.

This is horribly insecure. Compare a 6-digit number with a randomly generated

8-letter password containing uppercase letters, lowercase letters, and digits

– the latter has 218,340,105,584,896 possible combinations. It is trivial to

write a program that checks all million possible password combinations, easily

determining anyone’s PIN inside of one day. I verified this by writing a script

to “brute force” the PIN number of my own account.

The scope

Once an attacker has your PIN, they can take the following actions on your

behalf:

Read your call and SMS logs, to see who’s been calling you and who you’ve

been calling

Change the handset associated with an account, and start receiving

calls/SMS that are meant for you. They don’t even need to know what phone

you’re using now. Possible scenarios: $5/minute long distance calls to

Bulgaria, texts to or from lovers or rivals, “Mom I lost my wallet on the bus,

can you wire me some money?”

Purchase a new handset using the credit card you have on file, which may

result in $650 or more being charged to your card

Change your PIN to lock you out of your account

Change the email address associated with your account (which only texts

your current phone, instead of sending an email to the old address)

Change your mailing address

Make your life a living hell

How to protect yourself

There is currently no way to protect yourself from this attack. Changing

your PIN doesn’t work, because the new one would be just as guessable as your

current PIN. If you are one of the six million Virgin subscribers, you are at

the whim of anyone who doesn’t like you. For the moment I suggest vigilance,

deleting any credit cards you have stored with Virgin, and considering

switching to another carrier.

What Virgin should do to fix the issue

There are a number of steps Virgin could take to resolve the immediate, gaping

security issue. Here are a few:

Allow people to set more complex passwords, involving letters, digits, and

symbols.

Freezing your account after 5 failed password attempts, and requiring you to

identify more personal information before unfreezing the account.

Requiring both your PIN, and access to your handset, to log in. This is known

as two-step verification.

In addition, there are a number of best practices Virgin should implement to

protect against bad behavior, even if someone knows your PIN:

Provide the same error message when someone tries to authenticate with an

invalid phone number, as when they try to authenticate with a good phone number

but an invalid PIN. Based on the response to the login, I can determine whether

your number is a Virgin number or not, making it easy to find targets for this

attack.

Any time an email or mailing address is changed, send a mail to the old

address informing them of the change, with a message like “If you did not

request this change, contact our help team.”

Require a user to enter their current ESN, or provide information in addition

to their password, before changing the handset associated with an account.

Add a page to their website explaining their policy for responsible security

disclosure, along with a contact email address for security issues.

History of my communication with Virgin Mobile

I tried to reach out to Virgin and tell them about the issue before disclosing

it publicly. Here is a history of my correspondence with them.

August 15 – Reach out on Twitter to ask if there is any other way

to secure my account. The customer rep does not fully understand the

problem.

August 16 – Brute force access to my own account, validating the attack

vector.

August 15-17 – Reach out to various customer support representatives, asking

if there is any way to secure accounts besides the 6-digit PIN. Mostly

confused support reps tell me there is no other way to secure my account.

I am asked to always include my phone number and PIN in replies to Virgin.

August 17 – Support rep Vanessa H escalates the issue to headquarters after

I explain I’ve found a large vulnerability in Virgin’s online account

security. Steven from Sprint Executive and Regulatory Services gives me his

phone number and asks me to call.

August 17 – I call Steven and explain the issue, who can see the problem

and promises to forward the issue on to the right team, but will not promise

any more than that. I ask to be kept in the loop as Virgin makes progress

investigating the issue. In a followup email I provide a list of actions Virgin

could take to mitigate the issue, mirroring the list above.

August 24 – Follow up with Steven, asking if any progress has been made. No

response.

August 30 – Email Steven again. Steven writes that my feedback “has been

shared with the appropriate managerial staff” and “the matter is being looked

into”.

September 4 – I email Steven again explaining that this response is

unacceptable, considering this attack may be in use already in the wild. I tell

him I am going to disclose the issue publicly and receive no response.

September 13 – I follow up with Steven again, informing him that I am going

to publish details of the attack in 24 hours, unless I have more concrete

information about Virgin’s plans to resolve the issue in a timely fashion.

September 14 – Steven calls back to tell me to expect no further action on

Virgin Mobile’s end. Time to go public.

Update, Monday night

Sprint PR has been emailing reporters telling them that Sprint/Virgin have

fixed the issue by locking people out after 4 failed attempts. However, the

fix relies on cookies in the user’s browser. This is like Virgin asking me

to tell them how many times I’ve failed to log in before, and using that

information to lock me out. They are still vulnerable to an attack from anyone

who does not use the same cookies with each request. (ed: This issue has been

fixed as of Tuesday night)

News coverage:

This vulnerability only affects Virgin USA, to my knowledge; their other

international organizations appear to only share the brand name, not the same

code base.

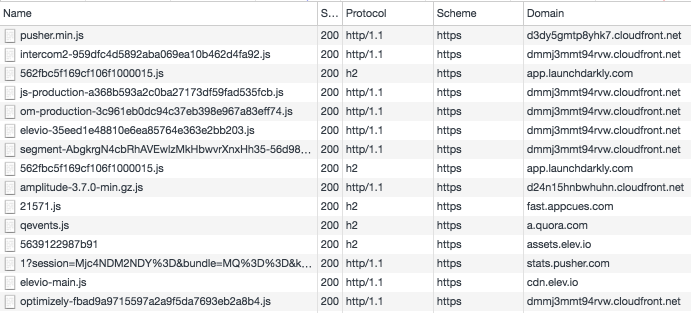

Update, Tuesday night

Virgin’s login page was down for four hours from around 5:30 PDT to 9:30 PDT.

I tried my brute force script again after the page came back up. Where before

I was getting 200 OK’s with every request, now about 25% of the authentication

requests return 503 Service Unavailable, and 25% return 404 Not Found.

Wednesday morning

Virgin took down their login page for 4 hours Tuesday night to deploy new code.

Now, after about 20 incorrect logins from one IP address, every further request

to their servers returns 404 Not Found. This fixes the main vulnerability I

disclosed Monday.

I just got off the phone with Sprint PR representatives. They apologized

and blamed a breakdown in the escalation process. I made the case that

this is why they need a dedicated page for reporting security and privacy

issues, and an email address where security researchers can report

problems like this, and know that they will be heard.

I gave the example of Google, who says “customer service doesn’t scale”

for many products, but will respond to any security issue sent to

security@google.com in a timely fashion, and in many cases award cash bounties

to people who find issues. Sprint said they’d look into adding a page to their

site.

Even though they’ve fixed the brute force issue, I raised issues with PIN based

authentication. No matter how many automated fraud checks they have in place,

PIN’s for passwords are a bad idea because:

people can’t use their usual password, so they might try

something more obvious like their birthday, to remember it.

Virgin’s customer service teams ask for it in emails and over the phone,

so if an attacker gains access to someone’s email, or is within

earshot of someone on a call to customer service, they have the PIN right

there.

If I get access to your PIN through any means, I can do all of the stuff

mentioned above – change your handset, read your call logs, etc. That’s not

good and it’s why even though Google etc. allow super complex passwords,

they allow users to back it up with another form of verification.

I also said that they should clarify their policy around indemnification. I

never actually brute forced an account where I didn’t know the pin, or issue

more than one request per second to Virgin’s servers, because I was worried

about being arrested or sued for DOSing their website. Fortunately I could

prove this particular flaw was a problem by dealing only with my own account.

But what if I found an attack where I could change a number in a URL, and

access someone else’s account? By definition, to prove the bug exists I’d have

to break their terms of service, and there’s no way to know how they would

respond.

They said they valued my feedback but couldn’t commit to anything, or tell me

about whether they can fix this in the future. At least they listened and will

maybe fix it, which is about as good as you can hope for.

Liked what you read? I am available for hire.